Why British politics feels so chaotic and what happens next

British politics is strange right now. The post-war party system that governed the country for eight decades has collapsed, but nothing has replaced it. Instead the old order shambles on, doing just enough to survive, but without any of the vital force that gave it life.

The signs are everywhere you look. Reform UK, a party with five MPs, leads national polls. Labour and the Conservatives combined can barely scrape support from 40% of voters – in the 1950s, they shared 90%. A Prime Minister who won a historic majority just a year ago is an even bet to be removed by next summer. This is British politics in the zombie era.

Since last year’s election, there has been no shortage of commentary on what is wrong with Britain. But nobody has answered the more fundamental question: why are all these weird things happening right now? Clearly there are some proximate answers: how have Labour become so unpopular so quickly? Poor decisions, internal divisions, lack of leadership. But why are their decisions so bad? Why are they so divided? Why is their leader so poor?

The answer is that we’re in a sort-of interregnum. The socio-economic foundations which provided the anchor for British politics in the second half of the 20th century – class loyalty, regional identity, generational party allegiance – have fallen away. But the electoral system, the party structures, the Westminster routines are still in place. From a distance, British politics looks recognisable. Up close, it’s obvious something is broken.

This period of transition won’t last forever, but while it does, it creates a strange kind of politics. Events that seem random – huge electoral swings, the constant churn of MPs and leaders, the rise of new political movements from nowhere – are all features of a political system without solid foundations.

It’s impossible to fully understand what is happening in British politics today and what is likely to come next without a framework that accounts for how the old party system has disintegrated.

The rest of this piece outlines the key characteristics of politics in the zombie era, as well as how we might break out of it. In future posts I’ll explain what the implications of this analysis are for anyone who wants to understand and influence UK politics in the coming years.

Everyone’s a swing voter now

Stable political systems require solid foundations. Britain’s post-war two-party system was ordered around class and regional identity, with party allegiance passed from one generation to the next.

In simple terms, Labour was the party of working-class voters in the cities and industrial towns of England, as well as Wales and Scotland. The Conservatives were the party of middle- and upper-class voters in suburban and rural areas, as well as almost all of the south of England.

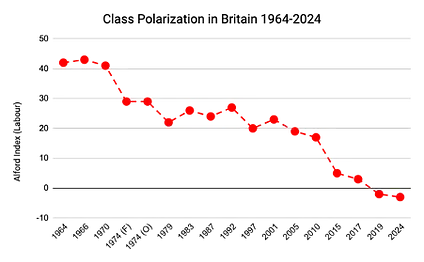

One way to measure class polarisation is the Alford Index. A score of 100% means that political allegiances are completely sorted on class lines, while a score of 0% means no class polarisation at all. In the early 1960s, the Alford Index was around 40. In last year’s general election, it was -3, meaning for the first time Labour’s vote was marginally more middle class than working class.

The Alford Index showing the class polarization of Labour’s vote in general elections

Class identity has eroded steadily, but the quirks of first-past-the-post mean that regional loyalties have often exploded suddenly. In 2015 it was Scotland; in 2019 the Red Wall; and in 2024 the Blue Wall. All of these traditional strongholds flipped almost overnight. There are still a few bastions of regional political identity in the UK, but evidence from by-elections and MRP forecasts suggests that even places like South Wales and Merseyside will follow the pattern before long.

Some argue that education has replaced class as the key axis of British politics. But education is a much weaker force today than class was even in the early 2000s. When you consider the vast differences in the social experience of going to university in the 1970s compared to the 2020s, that’s not surprising. As of today, British politics doesn’t have a meaningful social foundation.

And that’s why everyone is a swing voter now. Gone are the days when voters stayed loyal to a single party out of fear of what their grandparents, their trade union, or someone at the pub would think.

The Pedersen Index is a simple measure of electoral volatility. The past four elections (2015–2024) all have the highest scores since 1931 (after the Great Depression) and 1918 (after World War One). For the time being, volatility is a feature, not a bug, of British politics.

Some would argue that the relative freedom of the current era is an improvement on the rigid, class-dominated politics of the past eighty years. Voters are free to choose the party that best represents them and parties can no longer take whole groups of society or parts of the country for granted. For decades, the two main parties had a firm grip on voters, but now they’re slipping away.

The decline of the two-party system

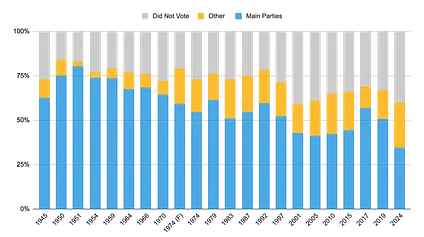

In the 1950 general election, 89% of voters supported either Labour or the Conservatives. Turnout was an impressive 84%, meaning that 75% of people across the country actively supported one of the two main parties. 1950 wasn’t exceptional: the two main parties won well over 80% of the vote throughout the 1950s and 60s.

In the 2024 general election, 58% of voters supported Labour or the Conservatives. Turnout was just 60%, meaning that overall 35% of the public supported the two main parties. In the most recent YouGov poll, the combined Labour and Conservative vote share was just 37%. Assuming a similar turnout to 2024, in an election held tomorrow just 20% of people would be voting for the big two parties.

The decline of the two party vote in the post-war era

This isn’t just another electoral cycle. Since the high-water mark of two-party politics in the 1950s, there’s been a slow but steady decline in support for the traditional parties. There have been rallies along the way – the two Brexit elections in 2017 and 2019 showed that in the right circumstances, voters will still turn to Labour and the Conservatives. But the overall trajectory is clear and the post-war party system is over.

The decline of the two-party system flows directly from the breakdown of its social foundations. Without the class loyalties and regional identities that guaranteed each party a base of support, Labour and the Conservatives have no right to exist. Mondeo Man, Workington Man, Stevenage Woman – the attempts to constantly find new electoral coalitions only prove how completely the old ones have disappeared.

Britain is ungovernable

Some people believed the 2024 election would show that the Conservative Party were the main source of chaos in British politics. With the “adult back in the room”, things would quickly return to normal.

Of course, this hasn’t happened. Keir Starmer is discovering what his predecessors found out: it’s now impossible to govern Britain without becoming deeply unpopular, fast. Starmer is the least popular Prime Minister in polling history after six months, beating out Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak. Whatever you think of Starmer’s qualities as a leader, it’s hard to argue that he’s literally the worst Prime Minister in modern history.

This again is a feature of the zombie era, not a bug. Consider the numbers: Starmer won his parliamentary majority with just 34% of the vote. Factor in turnout, and only 20% of registered voters actually backed him – fewer than any Prime Minister since Ramsay MacDonald in 1923, who lacked a majority and lasted less than a year. When you start with so few supporters and party loyalty no longer exists, you only need to add in a normal thermostatic swing away from government, and you get the most unpopular Prime Minister in history.

This is where the doom loop of Britain’s modern politics becomes clear. A fractured, multi-party democracy trapped in a majoritarian electoral system produces governments on ever-weaker mandates. And weak governments create anxious MPs, who know they might soon be out of a job.

Job insecurity

In the zombie era, Britain’s MPs live in perpetual fear. Under the stable two-party system most of them had real job security. While there were always a few marginal seats to worry about, stable electoral coalitions meant that for most MPs, winning an election meant a job for life.

When MPs didn’t fear voters, party leaders held the power. The biggest threat to an MP’s future would come from having the whip removed or simply being blocked from climbing up the ranks. As a result, backbench rebellions were rare. In the 1950s, there were entire parliamentary sessions without a single rebellion.

Today, the opposite is true. The 2024 election produced the largest number of new MPs in British political history. Based on current polling, the next election will break that record, with hundreds of first-time Reform MPs likely to replace hundreds of first-time Labour MPs.

This constant churn creates panic among new MPs. Watching their government immediately haemorrhage support, they feel the need to take action: voting down policies, forming campaign groups, eventually bringing down their leaders. After 2019, the new Red Wall Conservative MPs were widely seen as the most difficult to manage. Today’s new Labour MPs seem equally nervous.

Fears about job security are understandable – there will only be so many public affairs jobs for them to fill – but many MPs also suffer from a kind of Main Character Syndrome. Often representing places that have voted for their party for the first time in living memory, they seem to credit their own unique popularity rather than national factors beyond their control. They view themselves as uniquely gifted campaigners who can hold back the electoral tide through enough tweets about their constituency.

The rise of the political entrepreneur

Labour and the Conservatives are holdovers from the era of mass-membership, high-participation politics. They’re big, bloated organisations with weird rules on electing leaders and MPs, built for an era where electoral success required a broad appeal and communication with voters relied almost completely on the national media.

Political entrepreneurs are the opposite in every way. They’re movements built around charismatic individuals, with a threadbare or non-existent organisational infrastructure. They aim to succeed by targeting a narrow slice of the electorate, often by being sharply ideological or personality-driven. They rely on non-traditional media to reach voters who have tuned out from the BBC and ITV.

Nigel Farage is the archetypal political entrepreneur. He’s moved through a variety of barely functional populist parties, ending up with Reform UK, which until recently was simply a business that he held a controlling interest in. He’s made a political career out of a laser focus on immigration. And his political media strategy has combined a platform on GB News with an energetic use of TikTok.

The four independent Muslim MPs who won seats from Labour in 2024 follow the same pattern. They ran as independents with no formal political organisation. They campaigned almost exclusively on the issue of Gaza, and received no coverage from traditional media.

Zack Polanski might be the next political entrepreneur. Rather than start a party, he’s taken over one. His strategy, though, is fundamentally the same as Farage’s: narrow your focus to a small slice of the electorate – in this case, the 20% of voters who are clearly to the left of Labour – and use social media to get the attention the BBC won’t give you.

Where does this lead? One possibility is what’s happening in Dutch politics, where single-issue parties – an over-50s party, a farmers’ party, two animal rights parties – rise to prominence and collapse within a single electoral cycle. Or perhaps Britain follows the American path, where political outsiders take advantage of public frustration at the chaos and disruption of the zombie era.

There’s no going back

History tells us that moments of political transition can lead to all sorts of strange outcomes. The last time Britain found itself in a similar position was between the two world wars, a period that saw huge Conservative majorities, a Labour government with less than 200 seats, and a national government made up of all three parties.

So while Reform are ahead in the polls and look a reasonable bet to win the next election, there’s nothing inevitable about it. A Reform majority, a Labour majority, a Conservative majority, coalitions of all shapes and sizes – to rule out any of these would be shortsighted.

The more interesting question is not who wins the next election, but how the zombie era itself ends. What brings it to a close?

The post-war system worked because its political institutions aligned with social reality: a majoritarian electoral system for a world where voters neatly divided into two class-based blocs. To establish a new and stable order, then, something has to change. Either democratic institutions evolve to reflect a new social reality, or a new social reality emerges that can fit within our existing institutions, or both.

The most obvious route of democratic evolution would be a change in the voting system. Imagine the next election plays out as polls suggest: no party wins an overall majority, Labour and Reform win roughly 240 seats each, with a rump Conservative party of just 50 seats leaving a right-wing government short of a majority.

Instead, Labour turns to the Lib Dems and a group of 30 or so left-wing MPs formed from an electoral pact between the Greens and a Corbynite party. The price would be immediately implementing proportional representation. Germanifying British politics might well present its own problems, but a voting system that better reflects the fractured nature of British politics would provide a more stable foundation than the current one.

Of course, the political parties could pre-empt this transition without waiting for the electoral system to catch up. Electoral pacts between parties of the right and left could create a de facto proportional system. And if recent elections are anything to go by, voters – increasingly aware of local dynamics – may simply take matters into their own hands.

But perhaps Britain’s future looks more American than European. In this scenario, the chaos of a political system without firm anchors opens the door for a charismatic outsider to emerge as a kind of political singularity around which everything else operates.

In places like Hungary or Turkey, authoritarian leaders don’t just dominate politics – they are the organising principle for the entire system. Opposition parties that once competed on ideology or policy have merged into single broad-church coalitions. It’s a sort-of two-party system, but built around personality rather than class or ideology.

Britain has so far avoided a Trumpian cult of personality politics, but there’s no guarantee that this continues. A sufficiently charismatic leader could sweep away the remains of the old party system and become the new political centre of orbit. It might not be an appealing vision, but given Britain’s state of disorder, it’s not one that should be ruled out.

A third possibility is that new social or economic realities emerge to give politics fresh foundations. War, financial crisis, technological disruption – events that fundamentally reshape how people live and what they care about – can create new dividing lines for politics to organise around.

James Kanagasooriam’s analysis of the political geography of AI development highlights the possibility of a “collar flip”, where traditionally affluent white-collar workers begin to face economic disruption and insecurity at the hands of AI while skilled blue-collar workers find relative security.

It’s not hard to imagine AI’s transformation of work and society reshaping Britain’s political system in the same way as the Industrial Revolution did 200 years ago. In such a world, strange new coalitions might form: economically secure plumbers and electricians aligning with accelerationist software developers, while the Luddite accountant class demands support from the state. Data centres and chip factories could become the sites of political conflict in the way coal mines and nuclear power stations once were.

These scenarios might sound far-fetched, but that’s the point. The old framework for understanding British politics has broken down. The social anchors that made the system predictable – class loyalty, regional identity, party allegiance – have disappeared. What comes next is genuinely unclear.

But the zombie era could still last a while yet. The interwar period dragged on for two decades before a new settlement emerged. There’s no guarantee Britain finds stability quickly. But however long it takes, this moment is unusual. The post-war system was rigid – the same two parties, the same electoral coalitions, the same assumptions about what was possible. For the time being, all of that is gone.